Restraining Orders

Contents

- Overview

- First things first: Help give your state’s restraining order laws a tune-up

- Use WMC’s Grade Your State checklist to bring your state up to date

- How to support the federal Intimate Privacy Protection Act

- Understanding the connection between nonconsensual porn and domestic violence

- Combatting nonconsensual porn through state restraining order laws

- Do I need to pursue a restraining order to address nonconsensual porn, or are there other options?

- For WMC’s guide to Restraining Orders, WMC assumes that the victim lives in California. Why?

- I read WMC’s guide to Evidence Preservation and completed the Evidence Chart. Now, how do I get a restraining order?

- Do I seek a civil harassment or a domestic violence restraining order, and what is the difference?

- How do I enforce my restraining order?

- After being served with the TRO, the restrained person says he will stop the harassing conduct. Should I settle this case or continue to the hearing for a long-term restraining order?

- Court records are public records that anyone can find and read. Is there any way to keep the sensitive parts of my court filings private?

- Tips for completing your California domestic violence restraining order application

- Conclusion

-

Overview

Welcome to the second installment of WMC’s Something Can Be Done! guide. This installment focuses on restraining orders, criminal law and social change.

As WMC Advisor Danielle Citron urges:

‘‘We will look back at cyber-harassment as a disgrace — if we act now.’’

This guide will help you (as a citizen, legislator, officer, or judge) optimize your state’s legal system to ensure that your state safeguards its citizens’ ability to make a living, obtain an education, engage in civic activities, and express themselves – free from nonconsensual porn. It includes FAQs (geared toward victims, activists, judges, and law enforcement) and includes sample opinions, orders, documents where possible.

↑ Back to top -

First things first: Help give your state’s restraining order laws a tune-up

We’ve been asked the question: “Are the remedies that the legal system provides actually useful in nonconsensual porn cases?” This is an important question. A primary remedy provided by the legal system is money damages, and nonconsensual porn defendants are often judgment proof, meaning they have no ability to pay. In addition, most victims simply want the nonconsensual porn taken down immediately – not in a year, when the case goes to trial. But there are legal options that can provide quick relief. This section of the Something Can Be Done! guide covers one of them: restraining orders.

The restraining order system in many states is designed to be navigated by non-lawyers, so is relatively accessible. And it is designed to offer injunctive relief within days and sometimes hours to aggrieved parties. All that is needed is a little fine-tuning in each state so that each state has: (1) laws that work; (2) laws that are used; and (3) laws that are enforced. These three things are possible. California can serve as a model, where restraining orders are available for a broad range of digital abuse. This guide will teach you how to do what California has done.

↑ Back to top -

Use WMC’s Grade Your State checklist to bring your state up to date

To get us started, Without My Consent has developed the Grade Your State checklist – an action item checklist that, if completed by residents in every state, would go a long way toward solving the problem of digital abuse in America.

WMC’s Grade Your State checklist asks, “Is your state a place that safeguards its citizens’ ability to make a living, to obtain an education, to engage in civic activities, and to express themselves – free from nonconsensual porn?” There are nine (9) things every state should have in place in order to offer that security to its citizens. As far as we know, as of Fall 2016, California is the only state that receives a 9/9 score.1 The good news is that California provides a blueprint for safeguarding citizens from digital abuse that can be replicated across the states. If you join/support the groups identified in the checklist, and let your state government elected officials know that you care about stopping digital abuse, you will become part of the democratic process. It is easier than you think!

↑ Back to top- We would welcome more data on where America is today on the Grade Your State metrics. It would be helpful to know, for example, how many states meet 5 or more of the Grade Your State criteria). This could be a great research project for students. Please let us know your results! ↩

-

How to support the federal Intimate Privacy Protection Act

On July 14, 2016, Congresswoman Jackie Speier (D-CA) introduced the federal Intimate Privacy Protection Act (IPPA), and the bill will be reintroduced in 2017. If passed, the bill would make it a federal crime to distribute private, sexually explicit photographs or videos of people without consent, with some exceptions as listed in the statute.

“But wait,” you say, “I thought nonconsensual porn was a state issue? Why do we also need a federal law?” It is both a federal and a state issue. Here’s why.

State laws are important because nonconsensual porn is often perpetuated by ex-partners and domestic disputes are resolved in family court. The state prosecutors, investigators, and domestic violence advocates who handle these cases serve local communities and operate at the state level. At the state level, we need law enforcement who are funded and trained to handle crimes committed through the use of technology.

However, a federal law would fill a number of important gaps. Only thirty-four states and the District of Columbia have a nonconsensual porn law. And, of those states, some laws are poorly written to the point of being unusable or unconstitutional. The IPPA would bring clarity to the patchwork of state laws, strengthen existing regulations, and bring new protections to victims in states without them.1

If you want the federal IPPA to pass, you should contact your representative (http://whoismyrepresentative.com) and say something like, “Hi, My name is ___, and I’m one of Senator/Representative ___ constituents from ___. I’m calling to tell my Representative/ Senator that I think the Intimate Privacy Protection Act is important. Nobody deserves to have private intimate images posted online without their consent. I’d like to urge Senator/Representative ___ to join in supporting the Intimate Privacy Protection Act.”

↑ Back to top- Mary Anne Franks, It’s Time For Congress To Protect Intimate Privacy, Huffington Post (July 18, 2016), http://www.huffingtonpost.com/ mary-anne-franks/revenge-porn-intimate-privacy-protectionact_b_11034998.html. ↩

-

Understanding the connection between nonconsensual porn and domestic violence

Nonconsensual porn is the distribution or publication of individuals’ nude photos and videos without their consent. It denies victims the ability to decide if and when they are sexually exposed to the public.1 As Cindy Southworth, Executive Vice President at the National Network to End Domestic Violence (NNEDV) explains, “Long before the Internet, an abuser [in domestic violence situations] would issue a range of devastating threats: ‘If you leave me, I will kill the beloved family pet, kidnap the children, get you fired, ruin you financially, or destroy your reputation.’ The Internet allows offenders to terrorize their victims in front of a global online audience.”2 Nonconsensual porn is one way that abusers terrorize victims. According to the National Network to End Domestic Violence, 55% of programs reported that the survivors they work with have had abusers post sexually explicit images of them online without consent.3 According to the first national statistics on nonconsensual porn: one in 25 Americans has been a victim.4

Thanks to advocacy groups like the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative and Without My Consent, the public now recognizes that nonconsensual porn exacts a steep toll on the lives and livelihoods of its victims. It produces grave emotional and dignitary harms (in CCRI’s survey of cyber exploitation victims, 51% reported having suicidal thoughts), inflicts steep financial costs, and increases the risks of physical assault.5

Nonconsensual porn is a criminal issue, a domestic violence issue, a civil harassment issue, and a civil rights issue. It is the latter when nonconsensual porn is directed at a marginalized group in a way that reinforces their marginalization and undermines their equal participation in the benefits of society – which, it often is (90% of victims of nonconsensual porn are women and girls).6

Restraining orders are one of the most effective ways to combat nonconsensual porn.

↑ Back to top- Danielle Citron & Mary Anne Franks, Criminalizing Revenge Porn, 49 Wake Forest L. Rev. 345 (2014). ↩

- National Network To End Domestic Violence, NNEDV Praises Facebook for Banning Nonconsensual Pornography (Mar. 17, 2015), http://nnedv.org/news/4451-nnedv-praises-facebook-for-banning-nonconsensual-pornography.html. ↩

- National Network To End Domestic Violence, A Glimpse From the Field: How Abusers Are Misusing Technology (Safety Net Technology Safety Survey 2014), https://perma.cc/J974-2SXR. ↩

- Data & Society Research Institute | Center for Innovative Public Research, Nonconsensual Image Sharing: One In 25 Americans Has Been A Victim Of “Revenge Porn,” datasociety.net (Dec. 13, 2016), https://datasociety.net/blog/2016/12/13/nonconsensual-image-sharing/. ↩

- See Danielle Citron, HATE CRIMES IN CYBERSPACE Intro. & ch. 1 (Harvard University Press 2014); Cyber Civil Rights Statistics on Revenge Porn, at 2, https://perma.cc/LT2S-FAWE. ↩

- See Danielle Citron, HATE CRIMES IN CYBERSPACE 24–26 (Harvard University Press 2014); Mary Anne Franks, The Banality of Cyber Discrimination, or, The Eternal Recurrence of September (Apr. 3, 2015), http:// maryannefranks.com/post/115428385438/the-banality-of-cyberdiscrimination-or-the; Cyber Civil Rights Statistics on Revenge Porn, at 1, https://perma.cc/LT2S-FAWE. ↩

-

Combatting nonconsensual porn through state restraining order laws

Nonconsensual porn can be effectively addressed with courtissued restraining orders, provided that there is a robust legislative framework in place to support them. Such a framework requires at least three components: (1) laws that work (the responsibility of citizens and legislators); (2) laws that are used (the responsibility of lawyers and litigants); and (3) laws that are enforced (the responsibility of judges and the executive branch including law enforcement agencies).1 If you live in California, you are in luck. California has all of the Grade Your State checklist items in place to support a victim’s quest for justice.

If you live in a state other than California, we believe restraining order relief is possible in every state for a persistent and organized victim. We expect that there are restraining order experts in every state reading this guide who will know how to process the material we’re teaching and apply these skills in a state-specific way so that your state’s laws can be brought to bear in your county courthouse. That said, the higher your state scores on the Grade Your State checklist, the more likely it is that a nonconsensual porn victim will meet with success. If you live in a state other than California, you play an important part in the process of laying down a path to justice that gets steadier with repetition. The Grade Your State checklist shows WMC users how to bring their state up to code through activism.

↑ Back to top- There are federal law-based options for addressing nonconsensual porn, depending on the facts at issue. But for a variety of reasons (including that states have primary responsibility in family law matters), most cases in this area are handled in state and family courts, and therefore state law tends to be more widely used and to develop faster on these issues. ↩

-

Do I need to pursue a restraining order to address nonconsensual porn, or are there other options?

Although restraining orders are a very useful tool, and are the subject of this guide, there are other options available in every state. Police reports can be filed and civil suits can be considered at the same time that a restraining order is pursued. Nonconsensual porn victims will often work with support teams to seek justice via criminal law (see WMC’s 50-State and federal guides for your state; relevant California criminal statutes are described here) and/or civil lawsuits (see WMC’s 50-State and federal guides; relevant California civil statutes and common law are described here). Each victim should develop a strategy tailored to their particular goals and the defendant’s anticipated response.

↑ Back to top -

For WMC’s guide to Restraining Orders, WMC assumes that the victim lives in California. Why?

That’s our expertise. The authors of this guide are California lawyers and have deep expertise in navigating California’s legal landscape as it relates to nonconsensual porn. Rather than speak in generalities that might apply to every state, we opted to dig deep into California law with the expectation that there are restraining order experts in every state reading this guide who will know how apply the knowledge we’ve gained about California to their own state’s legal system.

California’s check-the-box Judicial Council forms apply to digital abuse.1 California also serves as a useful model because California has some of the strongest and most comprehensive laws pertaining to restraining orders in the country. Importantly, its digital abuse laws have been converted into check-the-box Judicial Council forms, which eliminates one enormous barrier to justice (money to hire an attorney). Form-driven relief is essential to affordable justice, and California Judicial Council forms make same-day restraining orders possible.

To make this happen, California lawmakers simply add a section to the relevant statute that instructs the California Judicial Council to develop forms for obtaining the relief provided by the statute. For example, California’s civil harassment law, Code of Civil Procedure, § 527.6(w)(1) & (2), instructs: “The Judicial Council shall develop forms, instructions, and rules relating to matters governed by this section.”2 In another example, California’s civil nonconsensual porn law, California Civil Code 1708.85, mandates the creation of Judicial Council form MC-125. See MC-125 here. This form gives nonconsensual porn plaintiffs an automatic right to proceed as a Doe Plaintiff and file certain records under seal for free, and potentially without the need to hire a lawyer. All states that are amending or passing new civil harassment, stalking, or nonconsensual porn laws can use this form-creating technique to build affordable justice into the legal system.

By pointing to California Judicial Council forms, we want to emphasize that form-driven digital abuse restraining orders can be highly effective (and in fact are highly effective in California). Please note that although California makes it easy for unrepresented parties to apply for and obtain restraining orders, every case is different, and even with a form-driven system, working with a lawyer can be an advantage, and in complex cases can be a virtual necessity. California courts often have an onsite self-help resource center, or a relationship with a Legal Servicesfunded clinic (see the next FAQ to pursue this option), that may be able to help you evaluate whether your case would benefit from legal representation, and that can help you navigate the restraining order system.

There is a lot of California case law on point. There is significantly more nonconsensual porn case precedent in California than in most other states for several reasons.

On the civil side, many digital abuse restraining order cases have been brought in California courts, in part because California has well-developed restraining order law generally. Many of the foundational civil and family court “matter of first impression” cases have already been litigated, and judges have ruled on issues including “Doe Plaintiff” litigation (meaning allowing a plaintiff to proceed anonymously or pseudonymously), the handling of private content, and the substantive laws that make nonconsensual porn unlawful. The law on nonconsensual porn is well-developed in California when compared to other states.

On the criminal side, the California Attorney General’s office has equipped law enforcement at the state and local level to deal with crimes committed through use of technology. In 2015 Attorney General Kamala Harris decided to make cyber exploitation a key part of her platform, and there were several successful criminal prosecutions3 – as well as a coalition of stakeholders working together to improve upon tech company policies – led by her office. See State of California Department of Justice, Office of the Attorney General online resource hub, at http://oag.ca.gov/cyberexploitation. This was a turning point for those who oppose revenge porn abuse.

As a result, digital abuse cases that previously were perceived as “tough” and legally “complex” have become somewhat less rare in California. Many family court lawyers, law enforcement, and family court judges have seen these issues before, and are increasingly familiar with strategies for handling such cases. These strategies can be replicated in every state, if state and federal laws are brought up to date.4

↑ Back to top- See Civil Harassment Prevention and Domestic Violence Prevention Court Forms, at http://www.courts.ca.gov/formnumber.htm. ↩

- See, e.g., the lower left corner of Judicial Council form CH-130, which reads:

Judicial Council of California, www.courts.ca.gov.

Revised July 1, 2014, Mandatory Form Code of Civil Procedure, §§ 527.6 and 527.9

Approved by DOJ ↩ - People v. Bollaert , No. CD252338 (Cal. Super. Ct. Dec. 10, 2013); People v. Meyering, No. CR169566 (Cal. Super. Ct. June 6, 2014); People v. Evens, No. 2486390 (Cal. Super. Ct. June 10, 2015). ↩

- See Danielle Citron, Expand harassment laws to protect victims of online abuse, Al Jazeera America (Mar. 21, 2015), http://america.aljazeera.com/opinions/2015/3/expand-harassment-laws-to-protect-victims-of-online-abuse.html. ↩

-

I read WMC’s guide to Evidence Preservation and completed the Evidence Chart. Now, how do I get a restraining order?

For Help In A Crisis:

If you are in danger, call 911. You may also ask a law enforcement officer for an Emergency Protective Order (“EPO”). California law authorizes a law enforcement officer to seek an EPO from a court 24 hours a day, seven days a week, if any person or child is in immediate and present danger of domestic violence or abuse, or in imminent danger of abduction by a parent or relative. An EPO is effective for up to seven days. The EPO must be entered into the California Law Enforcement Telecommunications System (CLETS). See Cal. Fam. Code §§ 6240 et seq.; 6380. The standard for granting an EPO is: (1) reasonable grounds to believe immediate & present danger of domestic violence, child abuse or abduction, elder or dependent abuse, or stalking or reasonable grounds to believe there is a demonstrated threat to campus safety, and (2) the EPO is necessary to prevent occurrence or recurrence of domestic violence, child abuse or abduction, elder or dependent abuse, stalking, or threat to campus safety. Cal. Fam Code §6251 & Cal. Pen. Code §646.91.For Help Obtaining A Restraining Order Tailored To Your Situation:

Find the people in your county who can help you get a restraining order. Request a meeting with them. Bring your Evidence Chart and binder to that meeting, and try to be as organized and efficient as possible. Here’s how.-

If you can afford to hire an attorney, this is a good time to do so. Get help finding an attorney.

-

If you cannot afford a lawyer, there may be resources in your state that are made available free of charge to qualifying victims. These may include: legal aid clinics/agencies/foundations, law school legal clinics, pro bono services offered by law firms, and self-help resources at your local civil & family law courthouse. Here are some specific options:

-

Call the National Domestic Violence Hotline 800-799-SAFE (7233): Ask for a list of domestic violence agencies in your state. Contact those agencies and ask whether they can help you secure a restraining order.

-

Go online to http://www.lsc.gov » What is Legal Aid » Find Legal Aid » Enter your address or zip code. This will give you a list of Legal Services Corporation-funded programs near you. The LSC-funded programs may provide free restraining order counsel to low-income Americans who qualify for services.

Example: A victim in San Mateo County, California would visit: http://www.lsc.gov » What Is Legal Aid » Find Legal Aid » Enter zip code “94063” » Find result: Bay Area Legal Aid

The victim would then call/email Bay Area Legal Aid and discover that Bay Legal offers a drop-in clinic that helps victims complete restraining order forms.

At the bottom of the Bay Legal intake form, it says: “Are There Pictures Or Other Material Of An Intimate/Sexual Nature On Social Media? If So, Speak To One of the Clinic Facilitators!” At that point, the victim would be connected with someone who could help her get a restraining order that covers digital abuse.

-

Apply to be a client of the Cyberharassment Clinic at New York Law School. The clinic represents victims of cyberharassment. You can visit the website http://nyls.edu/cyberharassment to find a contact sheet that will provide instructions for how to request representation.

-

Apply to be a client of K&L Gates’s Cyber Civil Rights Legal Project: The Cyber Civil Rights Legal Project is a global pro bono project that provides legal services to victims of nonconsensual pornography. You can visit their site http://www.cyberrightsproject.com and request consideration for representation by filling out the form.

-

Call the CCRI 24-hour Crisis Helpline 844-878-CCRI (2274): The Cyber Civil Rights Initiative (CCRI) provides counseling and technical advice to victims of nonconsensual pornography through its free 24/7 helpline for U.S. victims of nonconsensual pornography.

-

Contact your local courthouse for self-help resources. Answers to many of your questions should be readily available on your state court website’s self-help section. See, for example:

- California Judicial Branch: http://www.courts.ca.gov

- Self-Help: http://www.courts.ca.gov/selfhelp.htm

- Domestic Violence: http://www.courts.ca.gov/selfhelp-domesticviolence.htm

- Civil Harassment: http://www.courts.ca.gov/1044. htm

- For In-Person Help, Attend Your Local Court Clinic Hours (By County): http://www.courts.ca.gov/selfhelp-selfhelpcenters.htm. Bring your WMC Evidence Chart and binder!

-

-

-

Do I seek a civil harassment or a domestic violence restraining order, and what is the difference?

There are two types of restraining orders that are most likely to be available to victims of nonconsensual pornography: (1) a Domestic Violence Prevention Act (“DVPA”) restraining order, Cal. Fam. Code §§ 6200 et seq.; or (2) a civil harassment restraining order, Cal. Code Civ. Proc. § 527.6. There are several other types of restraining orders available in California that we list here for reference,1 but exceed the scope of this guide.

If you are eligible for a DVPA restraining order (see Cal. Fam. Code § 6211 for the required relationship), this is probably the way to go because DVPA restraining orders generally offer more protection, and are easier to get. We say that they are easier to get because the standard of proof is different. Civil harassment orders require “clear and convincing evidence” of harassment, Cal. Code Civ. Proc. § 527.6(i), whereas DVPA orders only require “reasonable proof of a past act or acts of ‘abuse.’” (Cal. Fam. Code § 6300.) In addition, the statutory definitions of abuse and harassment are different. Under the domestic violence statute, one nonconsensual porn act can constitute “disturbing the peace” abuse for which an order will issue provided the petitioner (aka the victim) can meet the burden of proof. Under the civil harassment system, a nonconsensual porn victim will most likely be arguing “harassment” by knowing and willful course of conduct, which requires: (1) a knowing and willful “course of conduct” (i.e., a pattern of conduct composed of a series of acts); (2) “directed at a specific person”; (3) “that seriously alarms, annoys, or harasses the person”; and (4) “that serves no legitimate purpose.” (Cal. Code Civ. Proc. § 527.6(b)(3).)

Although California law is relatively well-developed on nonconsensual pornography issues as compared to other states, what constitutes a “series of acts” under this standard is not entirely clear, nor is it entirely clear what it means for those acts to be “directed at a specific person.” For example, in creating nonconsensual pornography, a perpetrator must (i) create or obtain an image; and (ii) distribute or publish the image(s). Many smaller acts may be involved in carrying out those steps, which together, constitute a series of acts. However, some state harassment laws require that the series of acts include a direct communication between the defendant and the victim. Courts may disagree as to what constitutes a direct communication. See People v. Barber, 2013 NY Slip Op 50193(U), (Feb. 18, 2014) (dismissing charges against a man who posted his ex-girlfriend’s nude photos on Twitter and sent the photos to the woman’s employer and sister because he did not have direct contact with the victim). It remains to be seen whether any other courts in New York or elsewhere will adopt this view, and each case has different facts that may be important to decisions like this. Most cases are accompanied by direct communication so victims are often able to establish harassment for purposes of getting a restraining order without needing to address this issue.

To determine whether to proceed under domestic violence or civil harassment laws in California, a victim should consider the following issues with her support team.

- What is the burden of proof for the TRO?

- What is the burden of proof for the order after hearing?

- If domestic violence: What is the definition of abuse?

- If civil harassment: What action is covered?

- Who can petition? What is the required relationship?

- Who can be protected?

- What orders can be granted?

- What is the duration?

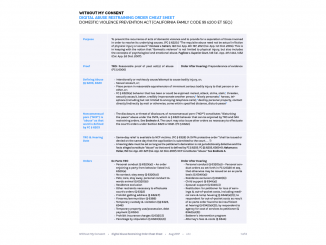

We have answered those questions for California in Without My Consent’s Digital Abuse Cheat Sheet. WMC’s Digital Abuse cheat sheet is a reference guide that you may find helpful, but is primarily aimed at lawyers who represent victims of nonconsensual porn. The cheat sheets provide answers to the questions that frequently arise in digital abuse restraining order cases and the legal support for those answers.

↑ Back to top- Restraining orders in California courts: Criminal Protective Orders (“CPO”); Emergency Protective Orders (“EPO”) (Fam. Code § 6240); DVPA Restraining Order (Fam. Code § 6200 et seq.); Civil Harassment Order (Code Civ. Proc. § 527.6); Elder Abuse (Welf. & Inst. Code §15600 et seq.); Workplace Protection (Code Civ. Proc. § 527.8); Juvenile Dependency Orders (Welf. & Inst. Code § 213.5); Military Protective Order; Tribal Protective Order (Title 10 of U.S. § 2265(a)). ↩

-

How do I enforce my restraining order?

Make sure your order is entered into the CLETS database: CLETS is an acronym for California Law Enforcement Telecommunications System (“CLETS”). It is a statewide protective-order database that is searchable by law enforcement agencies. The forms you’ll need to complete for getting a restraining order are available at http://www.courts.ca.gov/forms.htm. There are different forms for each type of restraining order proceeding, designated by letters like CH–, DV–, EA–, SV–, and WV. One of the required forms is a completed Confidential CLETS Information Form (CLETS-001). (Cal. Rules of Court, Rule 1.51.)

If the judge grants your restraining order, the information on the completed CLETS form will be entered into CLETS. When you receive your restraining order, check with court staff to determine whether you should walk the completed CLETS form to the clerk for database entry or whether the court will handle it for you. Just as officers can look up driving records during traffic stops, officers also can look up restraining order records when called to the scene of a domestic violence incident (provided the CLETS form made it into the database). During a domestic violence incident, if you notify the officer that a restraining order has been issued, that officer will be able to call dispatch to run a search on the CLETS database to pull the records for validation. Violation of a restraining order is a crime, separate and apart from whatever conduct prompted the police to respond, and in California should always result in an arrest being made.

To summarize, once you receive a domestic violence restraining order from the judge, give a copy of your restraining order to the local police, and keep a copy with you at all times. If there is a violation, call the police, file a police report, and report the violation to the court. The restrained party can be arrested, put in jail, and fined.

What is a non-CLETS order, and should I agree to it? Between the issuance of the TRO, and the hearing date, the restrained person (or their lawyer) may suggest that the parties compromise and ask the court to enter a “non-CLETS” order instead of a standard restraining order. The restrained party may believe that a non-CLETS order is less likely to appear on employment background checks because it never made it into the law enforcement database.

Protected parties should be aware that there is no formal provision in California law that specifically permits non-CLETS orders to be entered in domestic violence restraining order cases, and increasingly, courts across the states are refusing to approve or make non-CLETS orders in these cases. Why? There are two good reasons.

First, California Family Code § 6380(a) can be read to prohibit non-CLETS orders in domestic violence restraining order cases (and in all types of cases listed in § 6380(b)). When challenged, California appellate courts are critical of the lower courts that issued the non-CLETS order for which there was “no authority” (albeit all appellate opinions are not citable; ordered not published). The appellate court usually says something like the nonCLETS order should be “set aside” or is “appropriate for remand” so that the judge can “utilize the proper Judicial Council form....” On the other hand, we can infer from the existence of these cases that, on occasion, lower courts still do issue non-CLETS orders. If our research revealed eight appellate cases referencing them, then there are an unknown number where the nonCLETS order was issued and never challenged. Whether you consider this proposal is highly tactical. A non-CLETS order is not for everyone. It is probably only relevant in a very narrow set of circumstances (a compromise between two sophisticated parties represented by counsel, borderline facts, compassion for the perpetrator, and a reliable back stop if perpetrator breaches promise). Even then, if you do agree to such a compromise, your agreement should recognize that the judge may refuse to enter a non-CLETS order, and the parties should have a plan for how to proceed in that eventuality.

Second, judges don’t like non-CLETS orders because they don’t want to give victims a false sense of security. A non-CLETS order is probably not going to be enforced by law enforcement (because it never made it into the database). The victim would instead need to go back to court to enforce the order.

In general, getting the standard CLETS order is probably your best option. (Note: If the parties have other matters pending in family court, like a dissolution or a custody matter is also pending, the parties may propose to stipulate to a non-CLETS order under those case numbers.)

We have this conversation here because there is a lot of confusion, even among attorneys, about what a non-CLETS order means. The non-CLETS proposal comes up often in digital abuse cases. The restrained person (or their lawyer) asks for “one last chance,” or says “I can’t have this on my record.” If this is the request, and the victim is open to considering it, then a settlement agreement may be sufficient to address the needs of the parties. We discuss this option below.

↑ Back to top -

After being served with the TRO, the restrained person says he will stop the harassing conduct. Should I settle this case or continue to the hearing for a long-term restraining order?

There is a window of time – from the date the TRO issues up until the hearing date – during which the parties may be open to resolving the dispute by settlement agreement. Whether, and to what extent, a victim should engage in settlement negotiations is a complicated question. Each case is different and there is no absolute right or wrong course of action.

Procedurally, the dispute may be resolved by settlement if, for example, the parties negotiate a settlement agreement, and let the TRO expire. Such settlement agreements do not obligate law enforcement to make an arrest in the event of a violation, but may nonetheless be useful. Settlement agreements may allow parties to resolve more issues than can be addressed in the restraining order context (for example, other civil claims between the parties), and may contain restrictions on a party’s conduct that go beyond what a court is permitted to order. Settlement agreements can also afford the parties a great deal of latitude with regard to the remedies available for breach. However, the remedies for breach of a settlement agreement may not be as strong as for breach of a restraining order, or as straightforward to obtain. Though parties may consent to entry of a restraining order upon breach of a settlement agreement, getting the dispute back in court is not as straightforward, and success may not be as certain, as when a court-issued restraining order is violated.

If you are thinking about entering into a settlement agreement, you should consider hiring a lawyer to negotiate the terms for you. We say “hire a lawyer” for two important reasons. (1) There is a temporary restraining order in effect that prohibits contact between the restrained party and the protected party, which prevents direct negotiation. (2) It’s helpful to have a digital abuse lawyer advise on the promises around prohibited conduct (e.g., the restraining agreement provision) and promises around harm and remedies in the event of a future breach (the injunctive relief provision).

↑ Back to top -

Court records are public records that anyone can find and read. Is there any way to keep the sensitive parts of my court filings private?

Your options depend on what kind of court you are in (family court vs state court vs federal court), and what type of case you’ve brought (domestic violence restraining order vs civil lawsuit).

Civil lawsuit in state courts (other than California) or federal courts:

In civil courts, there are two primary strategies for protecting your privacy: proceeding pseudonymously (as a “Doe plaintiff”) and sealing/redacting intimate records. Both are typically accomplished by filing a motion with the court.-

Motion to proceed pseudonymously: You can ask a court for an order requiring that your identity not be revealed in the court filings. This is called asking for permission to proceed pseudonymously, or as a “Doe plaintiff.” Unfortunately, many courts do not provide an easy way to ask for this, and even if you file the proper paperwork obtaining permission to proceed pseudonymously can be an uphill battle depending on your state and the judge assigned to your case. The public’s interest in having access to court proceedings is strong, and you will need to demonstrate that your privacy interest outweighs it. But, this burden is not insurmountable. There are many factors that weigh in favor of the plaintiff’s “Doe plaintiff” request and a judge could readily find that a victim’s privacy considerations outweighs the public’s right to know her name in a nonconsensual porn case (see this list of discretionary factors federal court judges often consider in these cases). You simply have to brief the argument. For an overview of the case law in your state, see WMC’s 50-State Project on Filing Pseudonymously.

-

Motion for sealing/redacting intimate records: In addition to having an option to proceed anonymously, you can ask the court for an order that certain parts of the record be “sealed,” or not available to the public. Redacting is a way of sealing part of a document by “blacking out” the information that is to be kept private. For example, if you need to submit intimate photos of yourself to prove that someone posted them, you may ask to have those photos sealed or redacted. Having private/sensitive portions of the case record sealed may in some cases be easier than proceeding anonymously.

WMC sample motions: In states that don’t have ready-made forms, or for matters where forms don’t already exist, one or more motions will be necessary. Visit http://withoutmyconsent.org/resources/download-guide for generic sample motions for:

- Proceeding as a Doe Plaintiff in a California state court

- Sealing a record in a California state court

Different law may apply in different jurisdictions, and the facts of each case matter greatly, so this particular motion may not address all of the issues relevant to your case, but it will hopefully provide a head start for you and your attorney.

Civil lawsuit in California state court:

In California state court, the legislature has provided nonconsensual porn plaintiffs who allege a Section 1708.85 cause of action in their complaint, an automatic right to proceed as a Doe Plaintiff and file certain records under seal. See Confidential Information Form Under Civil Code Section 1708.85 (form MC-125). All states that are amending or passing new civil harassment, stalking, or nonconsensual porn laws can use this form-creating technique to build affordable justice into the legal system.Domestic violence restraining order in family court:

In family court, access to records is usually accomplished by local rules and customs.As an alternative to filing motions to proceed anonymously or to seal, you can in some cases rely on court practices and procedures to keep your filings relatively inaccessible to the public. For example, many family courts have rules stating that certain proceedings in them are confidential. However, these rules are relatively narrow in their applicability. On other occasions, courts may have a tendency not to make filings available over the internet. For example, in California, Rule of Court 2.503 concerns remote access to electronic court records. Subdivision (c) lists various records that are to be made available only at the courthouse. This list currently includes all protective order records. But, because more and more sources of information are being migrated to the internet over time, you should not rely on those practices lasting indefinitely.

Overall, you should weigh with your support team the pros and cons of the various strategies for protecting your privacy. What is the expense of writing a motion to proceed anonymously or to seal, and how likely are you to succeed? Sometimes there isn’t much legal precedent (past cases that the courts can look to for guidance) on this point and there may be significant uncertainty. However, the more obviously private/personal the information you want to shield is, and the more it relates solely to your private interests (as opposed to the public interest or being necessary to understanding the court’s rulings), the more likely it is that a judge will be disposed to grant your request.

↑ Back to top -

-

Tips for completing your California domestic violence restraining order application

You should start at the California Courts self-help page on how to ask for a restraining order: http://www.courts.ca.gov/1264.htm. The information below provides supplemental information that may be of use to digital abuse victims, but is not intended to replace any court forms.

Fill out the court forms and prepare to file. In a standard nonconsensual porn case, under Step 1, you will be completing at least:

- Request for Domestic Violence Restraining Order (Form DV- 100) (Partially completed Sample);

- Attach DV-100 Other Orders (a word document you create);

- Attach DV-100 Recent Abuse (a word document you create);

- Notice of Court Hearing (Form DV-109);

- Section 1, 2, and 3 of Temporary Restraining Order (Form DV- 110).

- Attach a second copy of the DV-100 Other Orders (a word document you create)

Follow the instructions in the Samples and you should be well on your way to getting a digital abuse restraining order.

Thank you.

↑ Back to top - Request for Domestic Violence Restraining Order (Form DV- 100) (Partially completed Sample);

-

Conclusion

Thank you for reading WMC’s Something Can Be Done guide. And, thank you, Digital Trust Foundation, for funding this practice guide so that readers across the US have access to best legal practices in digital abuse cases. In this guide, we have provided guidance that will help you put your best foot forward with the justice system. We’ve covered how to preserve your evidence, how to tell your story, how to build a local support team, and how to use copyright law, take down procedures and restraining order laws to seek justice through the courts.

It is your stories that fuel social change, and there is a dynamic relationship between your story and the larger stories it is a part of. WMC Advisor Danielle Citron describes a larger story:

Since the birth of the commercial internet in 1995, there has been this strong sense that all information must be free. That the internet would let us be whoever we wanted. That it would unleash our greatest liberties and rights. That we could be anyone we wanted to be. And, that we could be our best selves. That narrative is important. But, with time, we have also come to understand that it can be used to deny people of all of life’s crucial opportunities – the way that we can use the internet to work, to get jobs, to educate ourselves, to make friends and socialize and engage in civic engagement. We have come to understand that network tools can be used in a liberty enhancing or a liberty-denying and rights-denying way.

See Interdisciplinary Studies Institute Presents: Danielle Citron, amherstmedia.org, (2016), https://amherstmedia.org/content/interdisciplinary-studies-institute-pre....

These are real social problems, not to be trivialized or ignored. For too long, victims have been told “nothing can be done” at every turn. And that is simply untrue. WMC wants victims and their supporters to know everything that can be done on every level to combat nonconsensual porn. We turn the information in the SCBD guide over to you and your support teams to go for it!

We wish you the best and would welcome hearing about your results.

↑ Back to top